-

Birth name

Lillian Francis Beyl

-

Place of Birth

Columbus, Indiana, US

-

Place of Death

Indianapolis, Indiana, US

-

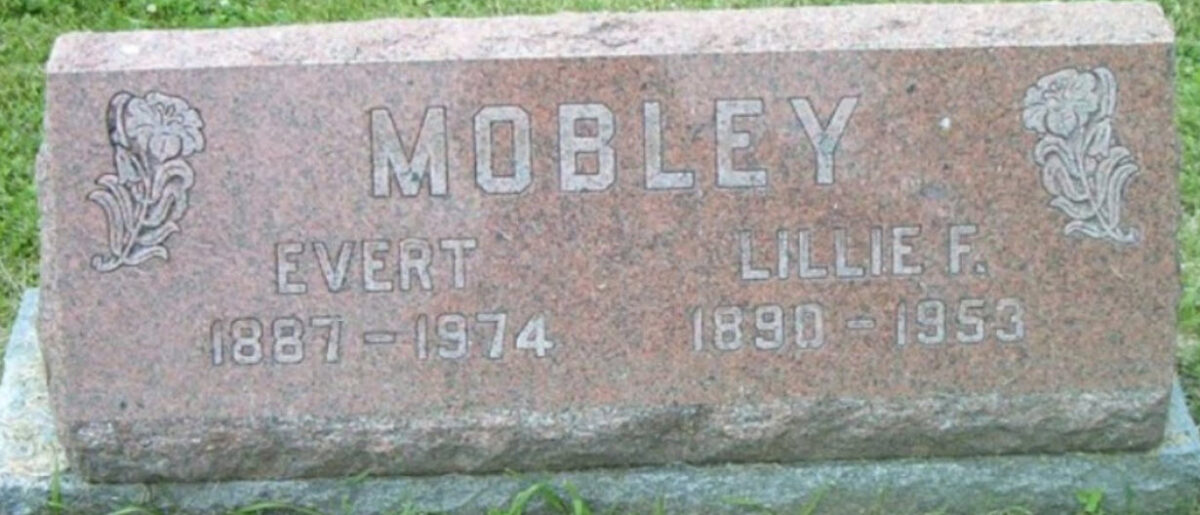

Burial Place

New Crown Cemetery and Mausoleum

🌸 Lillian Francis Beyl Mobley: A Matriarch in Motion

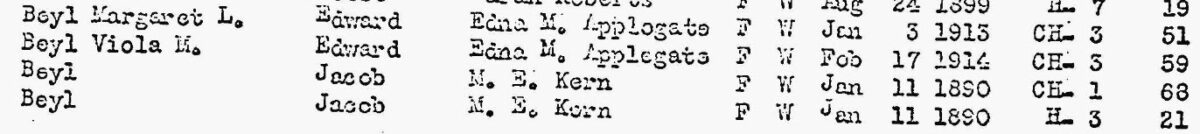

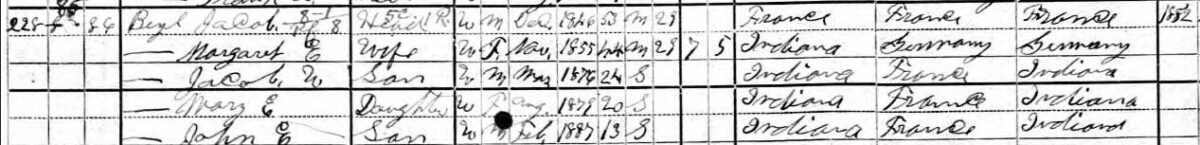

Born in the frost of January 1890, Lillian Francis Beyl came into the world quietly—so quietly, in fact, that the original record of her birth didn’t even bear her name. It simply listed the surname Beyl, the same one carried by her father, Jacob, a French immigrant carpenter with weathered hands, and her mother, Margaret Elizabeth Kern, born of German stock in Indiana.

One birth record. One child. But two listings. Could there have been twins once? A sibling who didn’t stay? The paper trail whispers, but does not explain.

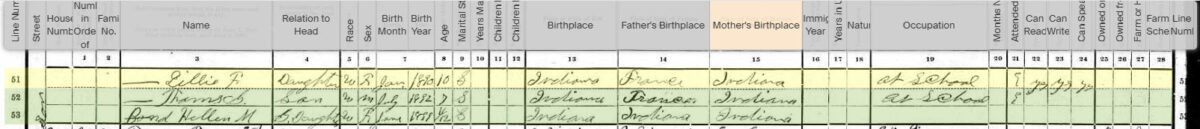

Lillie—known to family as such—grew up in a bustling home on Jackson Street in Columbus, Indiana, the middle of five surviving children.

Her father’s laboring years were taking their toll; by the turn of the century, he’d already spent months out of work. Still, Lillie’s world was likely full: the smell of sawdust, the murmur of French or German accents, the rhythm of a household run by necessity and love. A granddaughter, baby Helen, even joined the mix before Lillie had finished childhood.

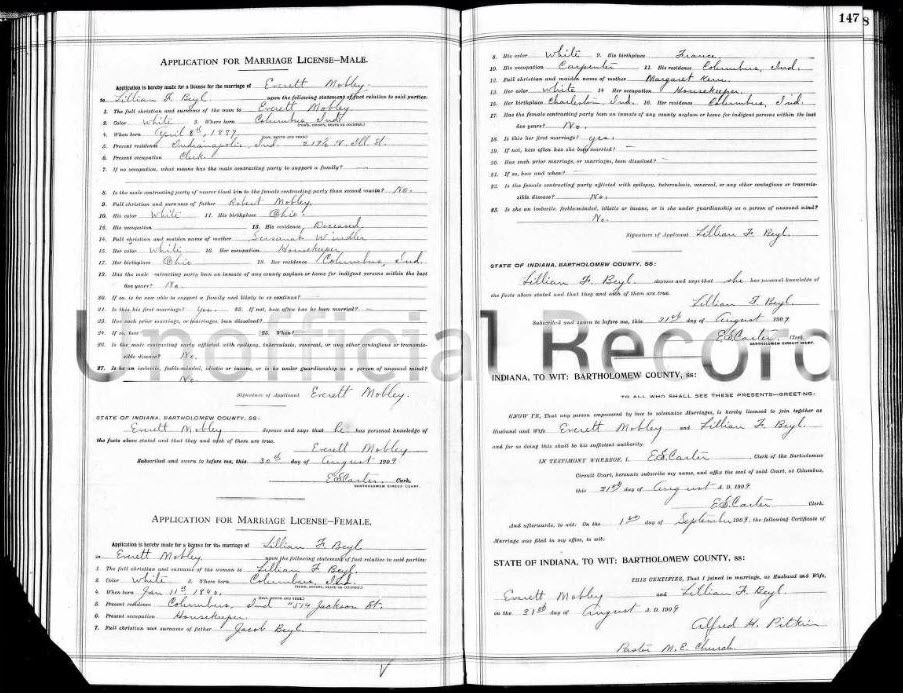

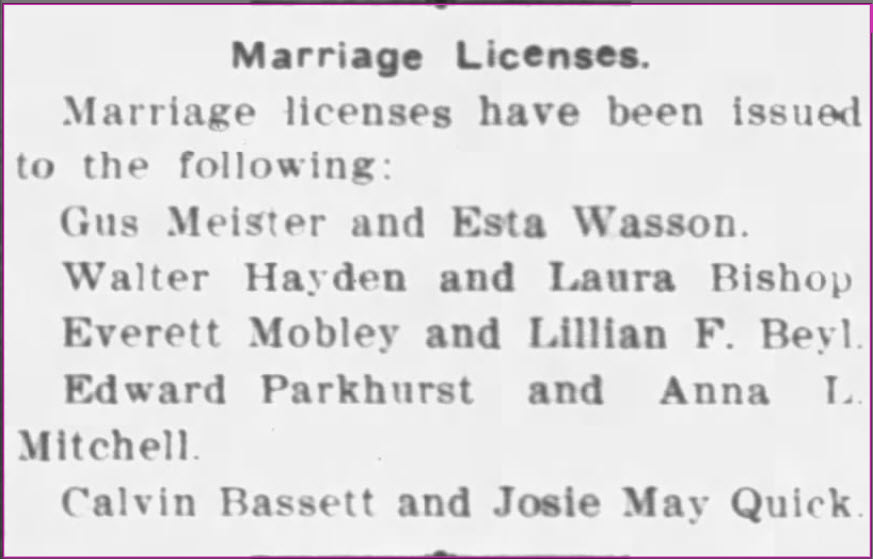

Marriage

At 19, she married James Everett Mobley, a clerk from Columbus. He was two years her senior, and together, they carved a life that moved from house to house, child to child, census to census.

In time, Lillie became what many women of her era were but rarely named—the spine of the home, the quiet architect of legacy.

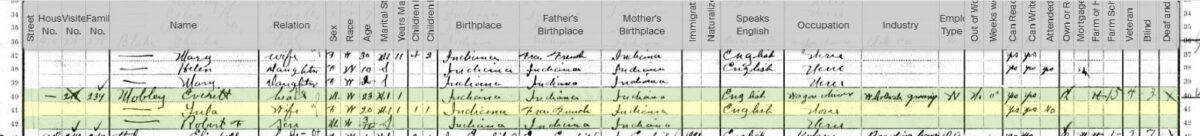

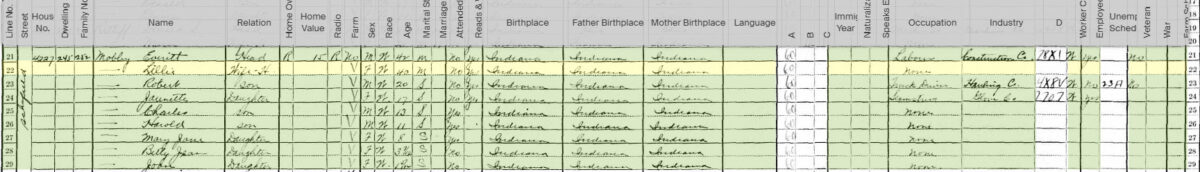

According to the 1910 United States Federal Census, Lillie lived with her husband and son on Bates Street in Center Township, Marion County, Indiana. Lillie was 20 years old at the time. Her husband, Everett, was 23, and their son, Robert F., was 3 months old. Everett worked as a Wagon Driver for Wholesale Grocery. The two had been married for 1 year, and Robert was their first child.

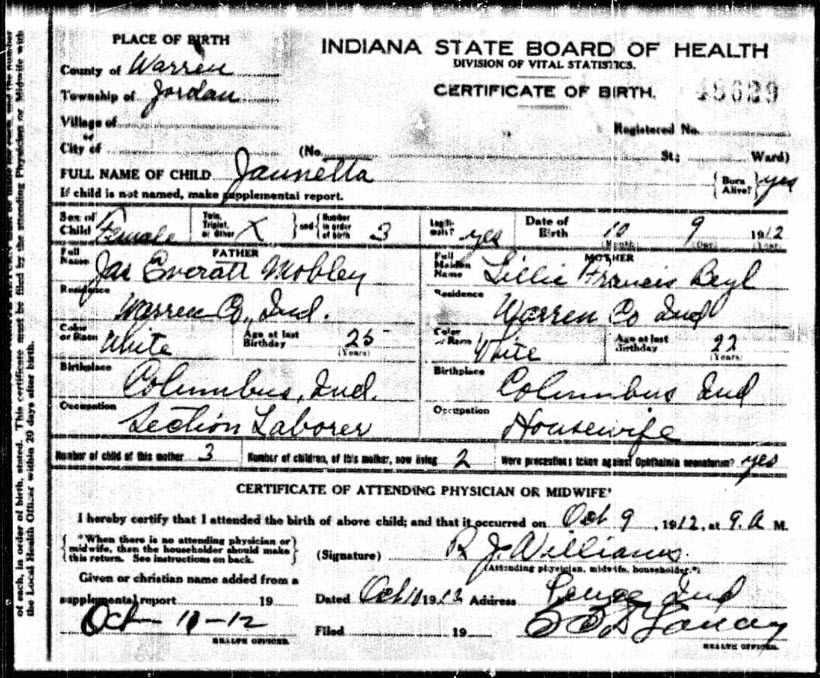

She gave birth to at least ten children. Some lived long, rich lives. Others—two unnamed babies—were born and lost before the ink could dry on their records. One of her daughters, Jaunetta, was possibly a twin herself. The mystery repeats.

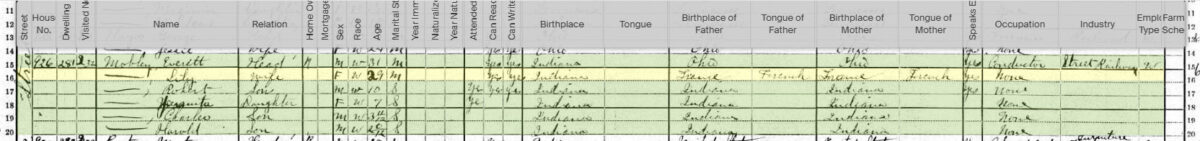

By 1920, the Mobleys had moved to Hasbrook Street in Indianapolis. Everett worked as a streetcar conductor. Lillie, a full-time housekeeper in the truest sense of the word, managed a household of four young children. As the family grew, so did the need for space, stability, and grace under pressure.

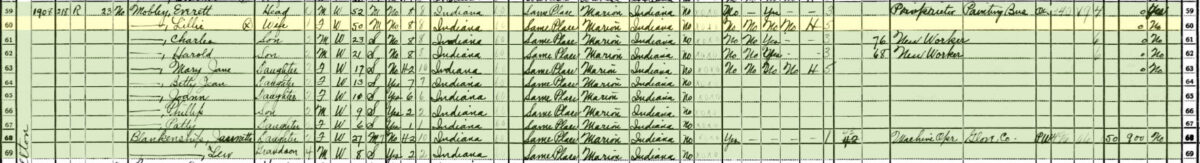

The 1930s saw seven children under one roof—including teenagers working as seamstresses and truck drivers to help sustain the family. The Great Depression may have knocked on their door, but the Mobleys stayed standing. In 1940, Everett started his own painting business. Lillie, at fifty, still had young children at home—and now, a grandchild, little Lew, under her wing too.

She saw it all: the rise of industrial Indianapolis, two world wars, the birth of Social Security, the migration of daughters into marriages and motherhood of their own. Through every change, Lillie held court in kitchens and front porches, her roots steady, her voice likely calm, her heart stretched wide.

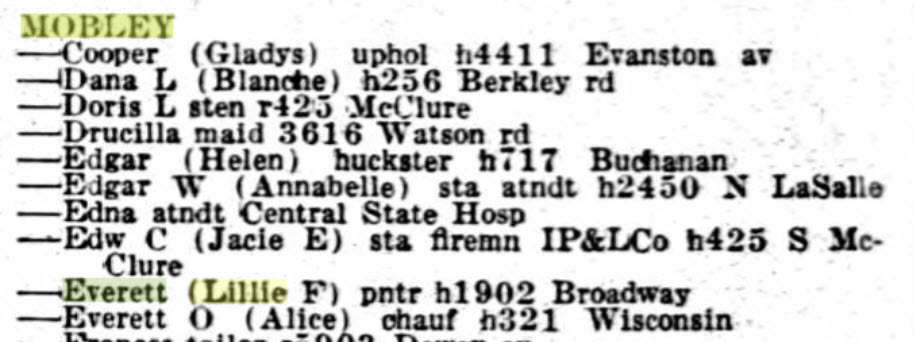

According to the U.S. City Directory, Everett and Lillie had moved to 902 Broadway St by 1942. Everett was still a Painter.

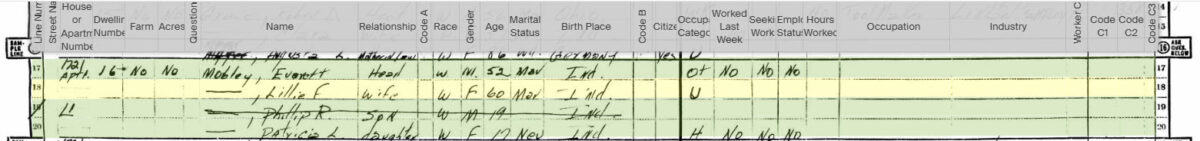

According to the 1950 US Federal Census, Everett and Lillie lived at 1721 Milburt St (might be Milburn) in Indianapolis, Indiana, Apartment 1. Everett was listed as 52, but it should be 62. Lillie was 60 years old at the time, and Everett was two years her senior. Also listed with them was their youngest son, Phillip R., 19, and their youngest daughter, Patricia L., 17. Phillip seems to be crossed out for some reason.

Death

She passed away in 1953, at 63 years old, in her home on West Washington Street. Her obituary named her children, her church, her faith. But it didn’t name what we can now see between the lines: the strength it took to mother through grief, to feed so many, to raise daughters into women and sons into men while holding the memory of those she lost. She rests beside Everett in New Crown Cemetery, the matriarch of a sprawling, ordinary, and extraordinary American story.

And still, she speaks—through census records, through handwritten certificates, through the smiles of her descendants. We may never know the sound of her laughter or the tilt of her voice when calling a child home for supper. But we know she was there, day after day, building a legacy from the bones of history.

Want to meet the woman behind the records?

Visit Lillian’s Introduction Page for a closer look at her life—from quiet mysteries to the legacy she left behind. Perfect for sharing with family and fellow memory keepers.

~Kris

☠️ Revisited by Bones

Ah, Lillian Francis Beyl—another ghost in the paper trail, but no less mighty in presence.

When I first dusted off her records, I found scattered footprints: a girl unnamed on her birth record, a woman reshaped by each census, a mother to many and mourned by more. No portraits remain, but the outline of her life is there—etched in the ink of birth ledgers, the margins of marriage licenses, and the faded whispers of loss.

What strikes me most is her stillness. Not the silence of obscurity—but the stillness of gravity. She was the kind of woman around whom stories spun—the kind who stitched generations together without ever writing a word.

They called her Lillie. But to me, she reads like the Matriarch of Memory.

I’ll keep listening. If you’ve got more to add—snapshots, secrets, or Sunday morning stories—I’ll be waiting in the archives, lantern in hand.

~ Bones

Lillian Francis Beyl

(1890 - 1953)